Labor Economics

Good Friday … For Labor and Job Statistics

The US economy added 162,000 jobs in March, the biggest net gain in over three full years. That’s good news right? Well, that depends on who you ask. Some say that it’s clearly good news, and that we’re finally moving in the right direction. But others say that the stats are superficial, and that they don’t address the underlying economic issues. I’m not sure what the real answer is, but one thing is for sure. The job market does seem to have a little bit more life. And sometimes, momentum can be a good thing.

The US economy added 162,000 jobs in March, the biggest net gain in over three full years. That’s good news right? Well, that depends on who you ask. Some say that it’s clearly good news, and that we’re finally moving in the right direction. But others say that the stats are superficial, and that they don’t address the underlying economic issues. I’m not sure what the real answer is, but one thing is for sure. The job market does seem to have a little bit more life. And sometimes, momentum can be a good thing.

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan recently agreed in an interview with Businessweek and said “there’s a momentum building up†in the U.S. economy and the odds of it faltering have “fallen very significantly.â€Â The Obama administration agreed. White House economic adviser Lawrence Summers said that “job creation will accelerate.” And Christina Roemer, chair of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers, said suggested that there’s a “gradual labor market healing.” And so it sounds like there may be a subtle wave of optimism that seems to be lingering.

That is definitely the case at business schools, where although recruiting numbers may be slightly down [(i) I don’t know for sure and (ii) It’s not over yet], they won’t be down by much. And during recruiting season, the students seemed to be pretty confident about their chances. Some of the ones I know did well. Many will be working at banks, consulting firms, Fortune 500’s, and start-ups. Even at the law school, things seem to be trending upward. It’s harder to tell exactly how things will play out, since law schools tend to do the vast majority of recruiting in the fall. But the message I’ve heard from most firms and organizations is that things will at least be a little better. I look forward to reporting the real news this fall.

That said, I don’t think these stories are necessarily compelling.

1. First, the administration has the herculean task of managing the negative sentiment that came from the past two year and balancing that with a more optimistm to keep people motivated and working hard, all while delivering a message that’s both truthful and transparent.

2. And more importantly, it’s not necessarily compelling because (i) the world of MBAs and JDs headed to become consultants, bankers, lawyers, fund managers, and non-profit leaders doesn’t reflect the overall economy. In fact, it’s really only a small fraction of the economy. The average person doesn’t attend a top 10 law or a premier business school nor do they hunt for six-figure jobs in their mid twenties, if ever. So many times, that person may end up jumping through a lot more hoops to get to the “promise land” of finding employment. (ii) And not only do these individuals represent a small percentage of the overall economy but they also have the advantage of undergoing a highly sophisticated recruiting process that starts well before interview season begins. A process where employers have coffee chats, luncheons, mixers, and receptions months before recruiting ever begins. And a process where hundreds of employers accept resumes, come to campus, and interview dozens of students on campus, all day. And sometimes multiple days. So taking a step back and looking at everything from a 30,000-foot, big picture view, I see that it’s a privilege to have the process in place.

So with a 30,000-foot view in mind, here are the objective arguments about the labor force, from both sides.

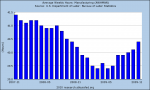

1. One on hand, the hard numbers from BLS do suggest improvement. (i) In total, employers added 162,000 jobs in March, the biggest monthly gain in three years. That’s always a good starting point. (ii) Manufacturing payrolls have also reportedly increased. (iii) This story is also true for heath care employers, who added ~27,000 full-time jobs and ~40,000 private-sector temp jobs. (iv) Surprising is that construction field held steady for the first time, after losing nearly ~865,000 last year. (v) Further, sources also suggest that the investment banks are finally starting to breathe again, and that broadening their scopes of services has helped them to decrease risk and squeeze out more revenues. (vi) And finally the unemployment rate is still down to 9.7%.

2. On the other hand, context suggests that the grass may only look greener. (i) I suspect we’re all aware that the number of jobs and hence total payroll numbers continue to skydive in financial industry. Venture capital and entrepreneurship numbers also remain low. (ii) However, even the numbers that are improving, according to US News, may really be more related to a reduction in labor force than an improving economy. (iii) But despite these more nuance calculations, even real growth number, according to some sources, are lower than expected. For example, forecasters expected ~200,000 new jobs in March, not 162,000. And that’s in spite of the fact that BLS reported more census takers this year than usual. Not only does that potentially positively change the accuracy of the reporting of the numbers but it also increases the number of actual jobs created. And coincidentally, these happen to be six-month temporary jobs, not full-time permanent jobs. While adding temp jobs is a good way for businesses to pick up and a good way for folks to earn a bit of cash, it also may not be indicative of any real economic trend.

In a recent post, Former Secretary of Labor said something similar. Rob Reich said “These are six-month temp jobs, and they tell us nothing about underlying trends in the labor market. It’s hard to gauge precisely how many were hired — probably between 100,000 and 140,000, although some estimates put the hiring as low as 48,000. Almost a million census workers will need to be hired over the next few months. Subtract these, and today’s job numbers are good but nothing to write home about.”

Conventional wisdom pinpoints that demand for such temporary employees increases during recessions and during recoveries, so employers can get the help they need, while also shining a spotlight on their budgets and reigning in expenditures. This may mean that we’re still somewhere in the middle. Either way, there’s still a lot of uncertainty and unfortunately, nobody has the million dollar crystal ball to lead us into the future.

In light of that, I think I like some of the positive signs. After all, psychology plays a big part in market movements and perhaps a bigger one in its recoveries. There are a lot of different ideas and competing opinions out there, a few are from experts, a good number from those who have agendas, a lot with a different perspectives than you or I have, and most of them with different levels and sources of research.

And in the end, how you frame the issues will affect [and possibly even change] your viewpoint.

Reflecting On The Economic Challenges Of 2009

2009 was an interesting year. I left my consulting job in the spring after finally deciding to return to business school and law school. And what timing! The financial crisis had just struck and the fear of recession left all of the business world scrambling. At the same Barack Obama had just made political and legal history with his historic presidential election. I was pretty excited at the chance to study these economic and political events, especially since I’d be enrolling in a JD-MBA program. But it became hard to remain so excited as I watched layoffs, bankruptcies, and unemployment begin to take over.

2009 was an interesting year. I left my consulting job in the spring after finally deciding to return to business school and law school. And what timing! The financial crisis had just struck and the fear of recession left all of the business world scrambling. At the same Barack Obama had just made political and legal history with his historic presidential election. I was pretty excited at the chance to study these economic and political events, especially since I’d be enrolling in a JD-MBA program. But it became hard to remain so excited as I watched layoffs, bankruptcies, and unemployment begin to take over.

Ever since the past summer, I’ve tried to keep up with the news, chat with my classmates, and solicit perspectives from industry professionals trying figure out exactly what’s going on. To be honest, I’m still not 100% certain, maybe not even 50% certain of everything that’s happening, as I’m by no means an expert on economic or labor issues. But I suspect that one’s viewpoint is pretty correlated to their experiences in the labor market, and sometimes it can be hard to see outside of that perspective.

For example, I had a discussion with a classmate from the investment banking industry (economics defines this as skilled labor) during the first week of class. We were discussing how recruiting was supposed to be down 40% – 50% this year, and his perspective was that everyone should really embrace the situation. That hard times create new opportunities, give new learning experiences, and spawn new ideas and companies.

In a second conversation, I talked with a family member who works in a position that earns an hourly wage (economics defines this as unskilled labor) and his employer had cut back his hours. Because of his situation, he empathized a lot more with those who were unemployed, and he suspects that the recovery will be a longer and a more difficult process, and that speeding it up requires a more of a collaborative effort to help people to find jobs. I think both perspectives are pretty valid.

But whether or not you agree with either perspective, the common denominator is that we are in pretty tough times now and that recovery will depend both on a collaborative effort and a willingness to consider new opportunities to solve the problem. Until now, MBAs have been contributing to the recovery mostly by forecasting unemployment rates, analyzing spending patterns, and predicting the market turnaround. And JDs have been looking at similar issues, but focusing on finding ways to use their technical skills with the law and policy skills to create change.

My opinion–for what it’s worth–is that given certain structural problems in the modern economy, many of these financial and legal tactics, while useful, may ultimately prove to do nothing more than to cover the wound, rather than address the bigger cultural issues that in recent history have influenced our levels of consumption, debt, and greed.

If business and law schools want to continue to play a role in the recovery, they should reflect on how these issues fit into the country’s top priorities. Over the last few decades, MBAs have flocked to the finance industry and law school graduates to corporate law (a field that works directly with the finance industry) both lured by six-figure salaries that are 3x (and more) the average wage. In return, these smart graduates have worked in roles that emphasize getting things done over learning, charge excessive rates for services, and structure deals to maximize profit. And because there was so much profit, other industries looked up to the industry and soon followed suit.

This mentality eventually made its way into the mortgage industry, and needless to say, as soon as its companies began to offer credit, Americans began to borrow. A lot. They applied for new lines of credit, bought new homes and cars, and got big screen TVs and went on vacations. Unfortunately, this era of growth was in some respects artificial. In the end, people overextended themselves financially, and eventually found themselves in too deep once the economy slowed.

In November, the media and administration became optimistic again and claimed that we were rebounding from the crisis and that jobs would be back in no time. I’m not so sure I agree. From my perspective, it seems as though there are far too many people out of work now, and the average length of unemployment is closing in on a year in some locations, a number will stay on the rise given the decreasing number of jobs.

One thing I’ve learned in the past two years watching much of this unfold is that one of the most important resource a company has in the long-term is still its people. And that resource needs to be prioritized right alongside profitability. This is true especially in challenging times because even when profits and the stock market are down, the stock of a company’s employees can be up. People can collaborate to come up with new ideas, they help a company adjust, adapt and change with the markets, they learn and implement new technology and promote innovation, and they can work together to accomplish more than their individual capabilities.

Unfortunately, the majority of Americans aren’t afforded the training or education to fine tune their management or critical thinking skills, so they end up in lower paying jobs, can’t save their money, remain in deep debt, and can’t positively impact the economy, while only a minority of Americans at the top thrive. Not only is this socially troubling but many also argue that in the long run it may also economically less productive.

This is certainly the view of the Obama administration, which is why the president wants to focus more on education and training and make decisions based on longer-term public investment. In his view, the economy does best when all Americans have the chance to increase in skill and contribute to the market. Many people agree with him ideologically but many also object because of the costs and the up front time investment.

Obama is also working with companies to adjust compensation plans to make them more fair and to reduce layoffs in the workforce, both of which are controversial with economists. Maybe his strategy stems from the idealism or aversion to risk that comes along with being trained as a lawyer. Or perhaps it’s easier for him to think that broadly since he’s not feeling the pressure of a collapsing industry on his shoulders. Perhaps it’s also because his shareholders are comprised of the broader population, and not financial investors, so his policy incentives are different. Who knows? But the interesting part to me is that both the policy (JD) and economic (MBA) perspectives seem critical in analyzing economic recovery.

And so both MBAs and JDs can play a major role in helping save the economy. As MBAs continue to look for profitable deals, invest in companies, and architect executive pay plans, they are also called to leverage profits to create jobs, use investments to steer innovation, and think more broadly about human capital and not just executives. Similarly, lawyers also have dual obligations. And instead of simply relying on facts and mitigation of risk to make decisions, lawyers must think more critically about the issues. They need to weigh the economic issues with the resulting social issues, think about how those issues affect a broader range of people, anticipate a wider range of possible outcomes, and then balance risk with those outcomes to come up with new policy plans.

Easier said than done? Perhaps. Brokering a balance between profit and social value, when there are diverse points of view and competing agendas is rarely easy. To lead America down that path requires leaders who are not afraid of change and who deeply believe that social values are just as important as economic value. I suspect that given our economy, more people will be open to change and aware of social values than ever before.

Personally, the recession has certainly forced me to reflect on change. Having old colleagues, friends, and family members directly affected by the market has made me more empathetic to those still in the workforce, especially those who don’t have education as a buffer.

Society should also take time to do some reflecting. And perhaps in 2010, society will decide that instead of focusing so much on pricing strategies and stock market gains, it will also start to focus on creating opportunities for education, promoting generosity in the midst of competition, and maximizing human potential, and not just profits. And in the end, perhaps these will pave the way for recovery to a more stable economy.

Business schools and law schools should welcome the opportunity to be at the forefront of this change.

Labor Day And The Economy

Maybe it’s because I’ve been insulated from the outside world ever since I’ve started law school, but I’m quite surprised that I haven’t been hearing more about the labor and employment issues in the middles of the biggest economic recession in recent history. In light of the fact that it’s Labor Day tomorrow, I thought I’d share my thoughts on US labor and the economy.

Maybe it’s because I’ve been insulated from the outside world ever since I’ve started law school, but I’m quite surprised that I haven’t been hearing more about the labor and employment issues in the middles of the biggest economic recession in recent history. In light of the fact that it’s Labor Day tomorrow, I thought I’d share my thoughts on US labor and the economy.

The latest employment figures came out September 4th, and the numbers are staggering. According to surveys, job losses continue to reach record levels — from 9.5% in July to ~9.7% now. Concurrently, merit increases have been frozen. In most industries, 4.0% pay increases have long been the standard … until now. Over the past year or so, wage growth has been closer to 0.5% and in some industries has flatlined at 0%. I saw these changes happening firsthand in my last consulting role, where more than half of my Fortune clients froze their merit increase pools, and nobody received salary bumps.

The unfortunate thing is that this number only represents those who still have jobs, and it doesn’t factor in that companies are decreasing worker’s hours, not paying bonuses, reducing 401ks, and demanding that employees go on furloughs (requiring workers to take unpaid vacations or to take one day off per week). I suspect about 20% of companies are employing these furloughs now, and at least to 50% of government companies. When I worked at the Attorney General’s Office this summer, the vast majority of people there were on the Friday Furlough plan. The US Post Office has requested that some employees take indefinite furloughs and they are offering incentive plans for people to retire as many as 10+ years early.

With all this in mind, I’m pretty surprised that I’m not hearing more about the economy or about the state of employment, especially this weekend. One explanation is the fact that “visible compensation†levels of the business class have not dramatically fallen. What I mean by “visible compensation†is the compensation numbers that make the Wall Street Journal or the news—CEO salaries, severance payments, number of stock options, and “expected†bonus levels.

But take caution in what you hear. From extensive experience studying the topic, I argue that these numbers are not representative of the American story. For the business class, what people don’t know is that cash compensation is usually a smaller fraction of a total pay package. Executives are usually highly reliant on “actual†bonuses and the appreciation value of stock options (not the delivery of options) as part of their paycheck. In fact, these often account for 50%-90% of their compensation packages. And despite Goldman’s recent record-breaking bonus payout this past summer, most firms are not handing out cash. Also, despite the thousands of stock options that executives are still receiving as part of their compensation arrangements, many of them are completely worthless. This is because option value for executives is based on the appreciation of the company, and in this economy companies are not appreciating. So despite popular perception and media frenzy about CEO pay, executives are also taking a huge cut in pay. That said, at least they can keep their heads above water with their 6-figure salaries even when everything else has gone awry.

For me, the real story is the middle class and the poor. The unemployment rate for these folks is a staggering 10%-16%, with African Americans and Hispanic Americans at the high end of the range. This is 2x to 3x higher than that of executives. The only outlier here is in the finance industry where everyone’s jobs and compensation are at risk.

Aside from job loss, the middle class’ portfolios are also declining. 401k plans have been dipping for the past year, health care plans are becoming more expensive, and the stock they do have is not performing well. But more important than that is the residential real estate bust, since homes are the primary assets of those in the middle class. Having spent a large amount of my life in two of the biggest real estate markets, California and Arizona, I’ve seen this first hand. In Arizona, the average decrease in home value is 35%-40%, the highest in the US. When I drive down the street of Arizona, I continuously notice homes for sale at 50% last year’s value and homes that have been foreclosed by the bank. On many streets, it’s half the homes. And California is no different. Home depreciation is hovering around the same range, even in nice neighborhoods like Berkeley, Santa Monica, and San Jose.

If so many Americans are losing their jobs, not getting increases in wages, loosing value in their homes, and subsequently in panic mode, what is going to incent people to spend money? I don’t know the answer, so I’ll leave that question to the economists working on it. What I do know is that that there needs to be a more focus on restoring the labor force in the middle class and because there hasn’t been most business are not safe. The one exception seems to be universities, especially top tier universities, where demand remains high, especially today as students hope to become more competitive for theses “odd†economic times. This is especially true for JD and MBA programs.

As I’ve mentioned in a couple of posts, I’m definitely fortunate to be headed back to school now. While here, I plan to take labor and employment classes at the law school as well as human capital and labor economics classes at the business school. I hope to be involved in these issues at the policy level one day down the line.

#EducationMatters

Please Vote

Recent Posts

Twitter Feed

Disclaimer

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Jun | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||